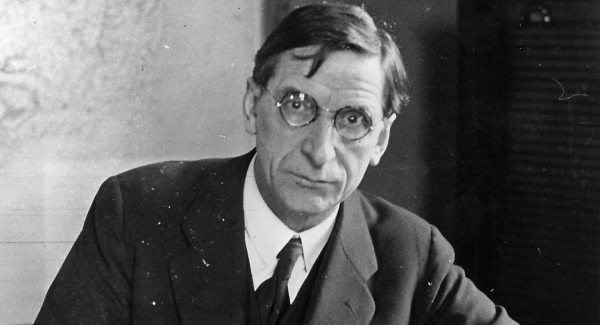

Irish historiography is currently going through an unprecedented ‘boom’ period. In particular, the ongoing ‘Decade of Centenaries’ has stimulated much new research in the history of the Irish Revolution. As we are seeing, this research is increasingly deploying innovative methodologies and theoretical perspectives. With the ‘Decade’ now in its latter stages, historians are now casting their eyes for new topics that can be re-assessed and re-evaluated. As we approach the centenary of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, it is, of course, understandable that historians may now wish to consider topics related to early independent Ireland. A key topic in the history of this period (c. 1922-60) is the person of Éamon de Valera: the central figure in Ireland’s twentieth century.

Tim Ellis (PhD candidate at Teesside University) explores where de Valera currently sits in Irish history and historiography and discusses how new research questions, methodologies and theoretical perspectives enliven the study of de Valera’s life and career

***

Éamon de Valera’s political career is indeed exceptional. It would not be unfair to say that de Valera dominated Irish politics between 1916-75, a period of nearly sixty years. De Valera rose to national prominence as the most senior surviving officer of the Easter Rising between 1916-7, with his status solidified by the defeat of the Irish Parliamentary Party at the East Clare by-election in July 1917. Later in 1917 de Valera became the Leader of Sinn Féin, and, the following year, lead the party to victory in the 1918 General Election. De Valera then spent nearly forty (non-consecutive years) as either Head of Government and/or Head of State. Between 1919-22 de Valera acted as President of Dáil Éireann/President of the Irish Republic, simultaneously Head of State and of Government. Between 1932-59, de Valera served as Head of Government: from 1932-7 as President of the Executive Council, then Taoiseach between 1937-48, again from 1951-4, and finally between 1957-9. He ended his career by serving two terms as President of Ireland (Head of State), between 1959-73. Perhaps the only time de Valera spent out of the political limelight was between 1922-6, a period which lasted from the outbreak of Civil War to the foundation of Fianna Fáil.

De Valera’s public eminence outlasted that of Mussolini, Stalin and Hitler. He rose to prominence before both the March on Rome and the Beer Hall putsch, yet unlike Hitler and Mussolini, he survived the Second World War. De Valera achieved national prominence before the October Revolution, and yet survived Lenin, Stalin and Krushchev. Indeed, de Valera was still President when Krushchev died in 1971. In a European context, only Francisco Franco and António de Oliveira Salazar (Portugal) are comparable, with both in power between 1936-75, and 1932-68 respectively. Franco was still an obscure Spanish army officer at the time of de Valera’s ascension to national political prominence between 1916-7, and yet both died in the same year. Perhaps the only politician with comparable staying power on the national stage is Fidel Castro. The Castro era (roughly from the revolution in 1959 to his death in 2016) is roughly comparable in length to the ‘de Valera era’ in Ireland.

De Valera currently ranks as one of longest-serving non-royal national leaders in history. Amongst non-royals since 1900, De Valera’s total (albeit non-continuous) time in office is bested only by Fidel Castro, Kim Il-Sung (North Korea), Chiang Kai-Shek (Republic of China/Taiwan), Yumjaagin Tsedenbal (Mongolia), Paul Biya (Cameroon), Omar Bongo (Gabon), Muammar Gaddafi (Libya), Enver Hoxa (Albania), Mohamed Abdelaziz (Western Sahara), Francisco Franco and Teodoro Obiang Nguema (Equatorial Guinea).[1.]

Significantly, no other democratically-elected leader, presiding over a constitutional regime which preserves the rule of law has served as long in office. Indeed, a recent monograph, by Mel Farrell, praises de Valera’s role in forging, consolidating and preserving Irish democracy. [2.] Only Lee Kuan Yew (Singapore) and Urho Kekkonen (Finland) are in anyway comparable. Both Finland and Singapore offering some interesting points of comparison with Ireland. Finland and Ireland have a similar population size and both previously existed under relatively lengthy, stable periods of foreign rule. Both Finland and Ireland emerged from destructive, divisive and traumatic civil wars in the early years of independence. Significantly, of the new European states to emerge from the First World War, Finland and Ireland were amongst the very few to preserve their democratic credentials. Singapore offers an interesting parallel, as an ex-British post-colony. Since independence, Singapore has implemented numerous socially conservative, authoritarian policies, which are not dissimilar to those of ‘de Valera’s Ireland.’ The democratic credentials of Singapore nonetheless, remain somewhat controversial, and according to Freedom House’s most recent ‘Freedom in the World’ index, Singapore can only be classified as ‘partly free.’ [3.]

To Kekkonen and Lee, as democratic leaders, we might also add Winston Churchill, who first joined the cabinet in 1906, and only retired in 1955, and thus had a political career of well over fifty years. Nonetheless, Churchill served less than a decade as Prime Minister, which seems rather minute when one considers the fact that de Valera served nearly four decades as Ireland’s Head of Government/Head of State. Whilst both men had lows in their careers, de Valera’s lasted for only four years (during which time he still remained as the leader of Sinn Féin). In comparison, Churchill’s ‘wilderness years’ lasted a full decade from 1929-39, during which time, his only formal position was as the MP for Epping.

Despite de Valera’s exceptionalism, there has been little historiography on the question of why de Valera’s political career lasted so long. De Valera’s exceptional status as a democratically elected political leader has not been rigidly analysed or interrogated. He has been the subject of numerous biographies, yet few scholars have offered explanations as to why de Valera enjoyed the extraordinary staying-power that he did. Despite his exceptional status, historians have preferred to evaluate de Valera’s achievements, rather than explain his exceptional political longevity. On the one hand, scholars such as Mary Bromage (1956), Frank Packenham and Thomas O’Neill (1970) have lauded de Valera’s career. [4.] Others, such as, Tim Pat Coogan (1993) blame de Valera for Ireland’s cultural and economic stagnation in the twentieth century. Coogan argues that ‘de Valera did little that was useful and much that was harmful.’[5.] Others have offered more balanced, nuanced evaluations of de Valera’s achievements. Diarmaid Ferriter’s Judging Dev (2007) reassess the way in which ‘“de Valera’s Ireland” became shorthand for all the shortcomings of twentieth century Ireland.’ [6.] Ronan Fanning’s biography (2015) offers a detailed and scholarly narrative, which largely agrees with Ferriter’s nuanced judgements. [7.] David McCullaugh’s recent two-volume biography (2017 & 2018), the product of much detailed, scholarly research, offers a balanced and thoughtful narrative of de Valera’s life, with several original insights on de Valera’s early years, which help to contextualise his later political career. [8.]

This question of de Valera’s longevity can only be answered by opening up several further research questions. As Anne Dolan has argued, the historiography of post-independence Ireland ‘is an historiography that is angry and disappointed with this past and perhaps Ireland’s problems throughout the twentieth century and into the twenty-first have made it hard to absolve the 1920s and 1930s.’[9.] She suggests that historians need to move beyond a history of this period in starkly evaluative terms. Dolan, instead suggests we should explore at a ‘bottom-up’ story of what the Irish people themselves ‘actually did,’ rather than a ‘top-down’ narrative of official and ecclesiastical oppression. Dolan’s insights into ‘de Valera’s island’ can be equally applied to de Valera himself. Answering the question of why de Valera was able to govern so long must invariably necessitate a bottom-up approach. All politicians, be they despots or democrats rely upon the people they govern for authority.

We cannot discuss de Valera without Fianna Fáil. Whilst there has been some work carried out on Fianna Fáil party structures and policies, the narrative has predominately been through a ‘high political’ framework, with little focus on how ordinary people participated in Fianna Fáil politics. [10.] Mike Cronin’s book on the Blueshirts (1997) offers an insightful story of how ordinary people participated in the movement. [11.] It uses interviews to explore motivations for joining and includes a whole chapter on the movement’s social life. Similar insights could be applied to Fianna Fáil. In its early days, Fianna Fáil enjoyed a thriving grassroots network, enabled through the branch or cumann structure. What was it like to be a member of a Fianna Fáil cumann? What activities (both political and social) did one participate in? How did membership of a cumannat a local level create and/or strengthen support for Fianna Fáil and de Valera nationally? These questions might be difficult to answer, but an oral methodology could hold out some hope. An oral history of Fianna Fáil in the 1950s and 1960s might be possible, as there will still be some veteran members alive with recollections of political life in this period. This in turn, could offer some insights on the latter stages of de Valera’s political career.

A significant area of activity amongst historians of Ireland in recent years has been the study of gender. With the recent publication of Aidan Beatty’s Masculinity and power in Irish nationalism, 1884-1938(2016) it is clear that analysis of de Valera’s masculinity could offer many new insights into his political power. [12.] Indeed as Joan Wallach Scott argues, ‘gender is a primary way of signifying relationships of power.’ [13.] For many historians of gender, discussions of race, through the idea ‘intersectionality’ have also proved useful. De Valera was born in the United States, and had a Hispanic father. This supplied useful ammunition for his detractors. Criticisms of the circumstances of de Valera’s birth blended concerns about race, gender and sexuality, and bear striking similarities with the ‘birther’ conspiracy around Barack Obama. Whilst de Valera’s race was, in some ways, a source of mockery, it equally made him appear exotic and exciting to his followers. As J. H. Thomas, the British Dominions Secretary, wrily noted, de Valera was the ‘Spanish onion in the Irish stew.’ [14.]

Political power and influence also strongly depend on image. A cultural, interdisciplinary history of the ways in which de Valera was represented in contemporary media and popular discourse would therefore be highly desirable. Whilst Mark O’Brien’s work (2001) on de Valera and the Irish Press explores the institutional aspects of the newspaper, there has not been much work on the ways in which the newspaper represented de Valera to the voters. [15.] There is also a well-established literature on the nature of political power in anthropology and sociology, with the writings of Clifford Geertz and Max Weber being well-established on the subject. [16.] Bruce Mazlish’s ideas about the ‘ascetic revolutionary’ could also easily be applied to de Valera. [17.] There is certainly more room for interdisciplinary work on de Valera, which incorporates perspectives from cultural studies, anthropology and political sociology.

My own research explores the significance of visual culture in Irish politics between 1922-39. In one of the chapters, I have focussed on the relationship between de Valera and visual culture. As it emerged, de Valera was a skilled manipulator of visual media. On a visit to the USA in 1927, de Valera, according to the Irish World ‘was photographed with his hat on and his hat off, full length and close-up. Quietly and seriously, he submitted to the ordeal, smiling once or twice as he obeyed the requests of the photographers.’ [18.] De Valera’s own newspaper, the Irish Presshad a high concentration of photographs. Indeed, I have estimated that during the election campaigns of the 1930s, the Irish Pressran 50% more images of politicians and political events than its rival, the Irish Independent.

Visual images of de Valera were mass-printed, manufactured and framed for supporters and voters. An advert in the Irish Press offered ‘a beautiful satin ribbon badge, with photo of de Valera and printed inscription “Ireland’s answer.”’ [19.] Indeed a young Irish student from the United Kingdom wrote to de Valera in 1937, declaring ‘I am one of your strongest supporters. I consider you as the finest leader Ireland has had yet… I have a picture of you in my room, it is taken from a journal and I have had it framed.’ [20.] As these examples show, like many leadership cults in modern political history, the ‘de Valera cult’ was transmitted through both visual and material culture.

This December marks the centenary of de Valera leading Sinn Féin to victory in the 1918 General Election. Next year also marks the centenary of de Valera becoming President of the Irish Republic. Hopefully these last few years of the ‘Decade of Centenaries’ will witness a flowering of new research into de Valera’s exceptional political career. As the past few years have demonstrated, centenaries have encouraged a new generation of historians to revisit topics and transform them by adopting new directions in their research: with new research questions, theoretical perspectives and methodologies.

There is, therefore, every reason to be optimistic about the future historiography of Éamon de Valera.

____________________________

Notes:

- https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/leaders-who-have-served-the-longest-terms.html. Accessed 24 Aug. 2018.

- See Mel Farrell, Party politics in a new democracy: the Irish Free State, 1922-37

(Basingstoke, 2017).

- https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2018/singapore. Accessed 24 Aug. 2018.

- Mary C. Bromage, De Valera and the march of a nation (London, 1956);

Frank Pakenham and Thomas Patrick O’Neill, Eamon de Valera (Dublin, 1970).

- Tim Pat Coogan, De Valera: Long fellow, long shadow (London, 1993), p. 693.

- Diarmaid Ferriter, Judging Dev: A reassessment of the life and legacy of Eamon de Valera (Dublin, 2007), p. 4.

- Ronan Fanning, Éamon de Valera: A will to power (London, 2015).

- David McCullagh, De Valera: Volume I: Rise, 1882-1932 (Dublin, 2017); David McCullagh, De Valera: Volume 2: Rule, 1932-1975(Dublin, 2018).

- Anne Dolan, ‘Politics, economy and society in the Irish Free State, 1922-39’ in Thomas Bartlett (ed.), The Cambridge History of Ireland, Vol. IV, 1880 to the Present(Cambridge, 2018), p. 330.

- See, for instance, Richard Dunphy, The making of Fianna Fáil power in Ireland, 1923-48(Oxford, 1995);

Kieran Allen, Fianna Fáil and Irish labour(London, 1997);

Donnacha Ó Beacháin, The destiny of the soldiers: Fianna Fáil, Irish republicanism and the IRA, 1926-73 (Dublin, 2010);

Noel Whelan, Fianna Fáil: a biography of the party(Dublin, 2011).

- Mike Cronin, The Blueshirts and Irish politics (Dublin, 1997).

- Aidan Beatty, Masculinity and power in Irish nationalism, 1884-1938 (London, 2016).

- Joan Wallach Scott, ‘Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis’ in American Historical Review, vol. xci, no. 5 (1986),p. 1067.

- Ferriter, Judging Dev,p. 106.

- Mark O’Brien, De Valera, Fianna Fáil and the Irish Press(Dublin, 2001).

- See Clifford Geertz, Kings, centres and charisma: reflections on the symbolics of power (London, 1993);

Max Weber, The theory of social and economic organisation, trans. Talcott Parsons and Max Henderson (Oxford, 1947).

- Bruce Mazlish, The revolutionary ascetic: evolution of a political type (New York, 1976).

18.Irish World, 12 Mar. 1927.

19.Irish Press, 24 Mar. 1932.

- Letter from Patrick J.R. Kennedy to Éamon de Valera, 14 October 1937 (UCDA P150/2435).