Eimear Rosato tells us about her MLitt research into memories of conflict in North Belfast

My MLitt research project at Newcastle University was concerned with the intergenerational memories of conflict: essentially how memory was passed down through the generations influencing young people today.

Intergenerational memory has come to the forefront of political discourse in recent years. In recent debates at the Féile an Phobile festival in West Belfast, the issue of how conflict has affected young people was raised many times, thus highlighting its prominence in Northern Ireland.

There are many interwoven themes surrounding the memory of the Northern Ireland conflict, such as identity, segregation, mental health and sectarianism. My research used Ardoyne, a small Catholic enclave in North Belfast as a case study and considered how each of these themes impact on young people in this community today and concluded with a reflection on how the young people themselves see the community moving forward in a ‘post-conflict’ era.

The theorist Karl Mannheim argued that people belonging to the same generation share a common location in the social and historical process. He argued that this predisposes them to certain characteristic modes of thought and experience. Their common situation becomes the basis for their group solidarity within the generation; and, in turn, this becomes their ‘generational ideology.’ Paul Thompson has explored the idea of intergenerational memories, characterising them as ‘accounts of past events that are passed on from one generation to the next in a family, nation or community by means of stories.’ Storytelling therefore became the basis of my research with many of the interview questions being based around the stories their families would tell.

Hamber and Kelly found that community storytelling in NI plays a fundamental role in dealing with the past and transitional justice processes.(1) In other countries, it has been noted that oral historical traditions facilitate fluidity in the cross-generational transmission of past injustices, transforming storytelling and commemoration into critical sites for motivating political mobilisation.(2) Connerton argues that ‘acts of transfer’ transform history into memory and enable-shared memories across individuals and generations. The stories reinforced the community’s narrative of the conflict on the younger generations to ensure their stories endured. In my own research, many of the interviewees told me of the stories they knew, with one incident cropping up again and again, the burning of Hooker Street. One interviewee went further, arguing that: ‘I know the story of the streets burning so well it was as if I was there’.(3)

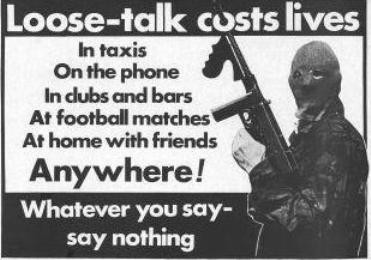

Although storytelling provided the foundations of the majority of the interviewees’ knowledge of the conflict, many interviewees also discussed the silence which existed around the conflict. As Lundy and McGovern highlight, prior to their research in the Ardoyne Commemoration Project, many individuals and families struggled privately and silently with unresolved issues surrounding the conflict.(4) These authors also note that there were ‘taboo subjects’ and that silence prevailed in this regard at the individual, family and community level. This was most evident in the families that had experienced a conflict-related death; for many in NI there is a ‘culture of silence’.(5) In my research, an interviewee mentioned the private nature of her family – ‘my granny always told me “loose lips cost lives”’.(6) She went on to discuss how closed off her immediate and extended family were, even to her when she asked personal questions, always answering ‘what do you want to know that for?’ The Commission for Victims and Survivors argues that this silence and privacy may stem from the perceived danger of talking about the conflict. The fear of repercussions of talking is exemplified within the IRA posters found in the Linen Hall Library.

(Image: ‘Loose talk costs lives’- IRA poster during the Troubles. Image credit- [https://irishelectionliterature.com/2011/12/23/loose-talk-costs-lives-and-other-republican-ira-posters/] [Accessed November 15, 2017])

Community projects, taking place with young people in Ardoyne are trying to overcome the ‘fear factor’ and mistrust of the other community. Cross-community projects such as those conducted by Ardoyne Youth Club aim to provide hope the young people. In my research, one interviewee referenced the projects between Ardoyne and the Protestant/Unionist Hammer Youth Club. Several interviewees made reference to the RCity project. For them, this inspires hope for change, progress and building bridges between the deeply divided communities. They expressed hope that the forward-looking (rather than backward-looking) mindset of young people will enable the community to overcome the sectarian, segregated legacy left by the conflict.

However, intergenerational memory is a complex term with many interlinking themes, many of which I have not discussed here. For Ardoyne, place and space, cultural memory and community memory all play vital roles in impacting on younger generations and on how Ardoyne and Northern Ireland move forward in the future. With the government of Northern Ireland currently caught in a complex political deadlock, the issue of memory has come to the forefront once again. If politicians cannot agree because of issues arising from the past, then the ability of society and young people to move forward comes into question.

References:

(1) Elizabeth Baumgartner, Brandon Hamber, Briony Jones, Grainne Kelly and Ingrid Oliveira, “Documentation, Human Rights and Transitional Justice,” Journal of Human Rights Practice 8 (2016), p. 4.

(2) Linda Farthing and Benjamin Kohl, ‘“Mobilizing Memory”: Bolivia’s Enduring Social Movements’, Social Movement Studies 12: 4 (2013), 364.

(3) Interview four with the author, November 9, 2016.

(4) Patricia Lundy and Mark McGovern, ‘“Participation, truth and partiality”: Participatory action research, community-based truth-telling and post-conflict transition in Northern Ireland,’ Sociology, 40:1 (2006), 75.

(5) Lundy and McGovern, ‘The politics of memory in post-conflict Northern Ireland’ Peace review: A journal of social justice, 13:1 (2001), 33.

(6) Interview one with author, November 1, 2016.

(7) Ibid.